50TH ANNIVERSARY OF OM

In memoriam Fredy Studer

1972 – 2022

Am Montag 22. August ist der Luzerner Schlagzeuger Fredy Studer (1948) nach einer schweren Krankheit unerwartet schnell gestorben. Der international bekannte Musiker zählte in den letzten 40 Jahren zu den herausragenden Schweizer Schlagzeugern im Bereich Jazz und Improvisation. Studer war ein Musiker mit einer schier unerschöpflichen Kraft und Energie, mit denen er zahlreiche Bands und Projekte zum Abheben brachte. Studer war musikalisch breit interessiert: Jazz, Rock, Improvisation, Elektronik, Neue Musik gehörten zu seinen bevorzugten Domänen.

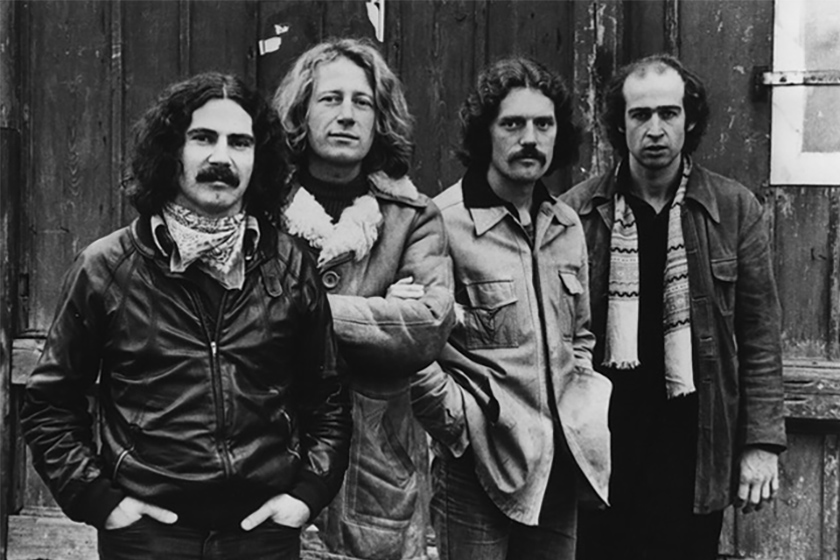

Fredy Studer hat mit der 1972 gegründeten Electricjazz-Freemusic Band OM, die diesen Herbst mit einem neuen Album ihr 50 jähriges Jubiläum feiert, Schweizer Jazzgeschichte geschrieben. Das Quartett mit Christy Doran, Urs Leimgruber und Bobby Burri zählt europaweit zu den langlebigsten Formationen. Zu seinen wichtigsten Bands gehörten auch das Trio „Red Twist & Tuned Arrow“, das Hardcore Chambermusic Trio Koch-Schütz-Studer sowie seine eigene Band Phall Fatale. Studer spielte mit zahlreichen Koryphäen wie Joe Henderson, John Abercrombie, Miroslav Vitous, Pierre Favre, Jojo Mayer, George Gruntz, Jack deJohnette, Charlie Mariano, Robyn Schulkowsky, Joey Baron, Jürg Halter, Roberto Dominiconi und vielen anderen.

2018 veröffentlichte Fredy Studer sein Solowerk „Now’s the Time“ auf dem er die Subtilitäten und ausgetüftelten Grooves seines Schlagzeug- und Perkussionsspiels umfassend auf den Punkt brachte. „Now’s the Time“ war auch die Devise, wie Fredy Studer dachte und lebte. Die Präsenz im Moment, die Kraft der Unmittelbarkeit, die Energie der Improvisation: Das war sein Ausdruck, sein Lebenselixier.

„Now’s the Time“ heisst nun auch Abschied zu nehmen von einem Schlagzeuger, Musiker und lieben Menschen, den seine Partnerin Katharina Amrein und zahlreiche Musiker und Musikerinnen, Freundinnen und Freunde extrem vermissen werden.

Pirmin Bossart

Oktober 2023

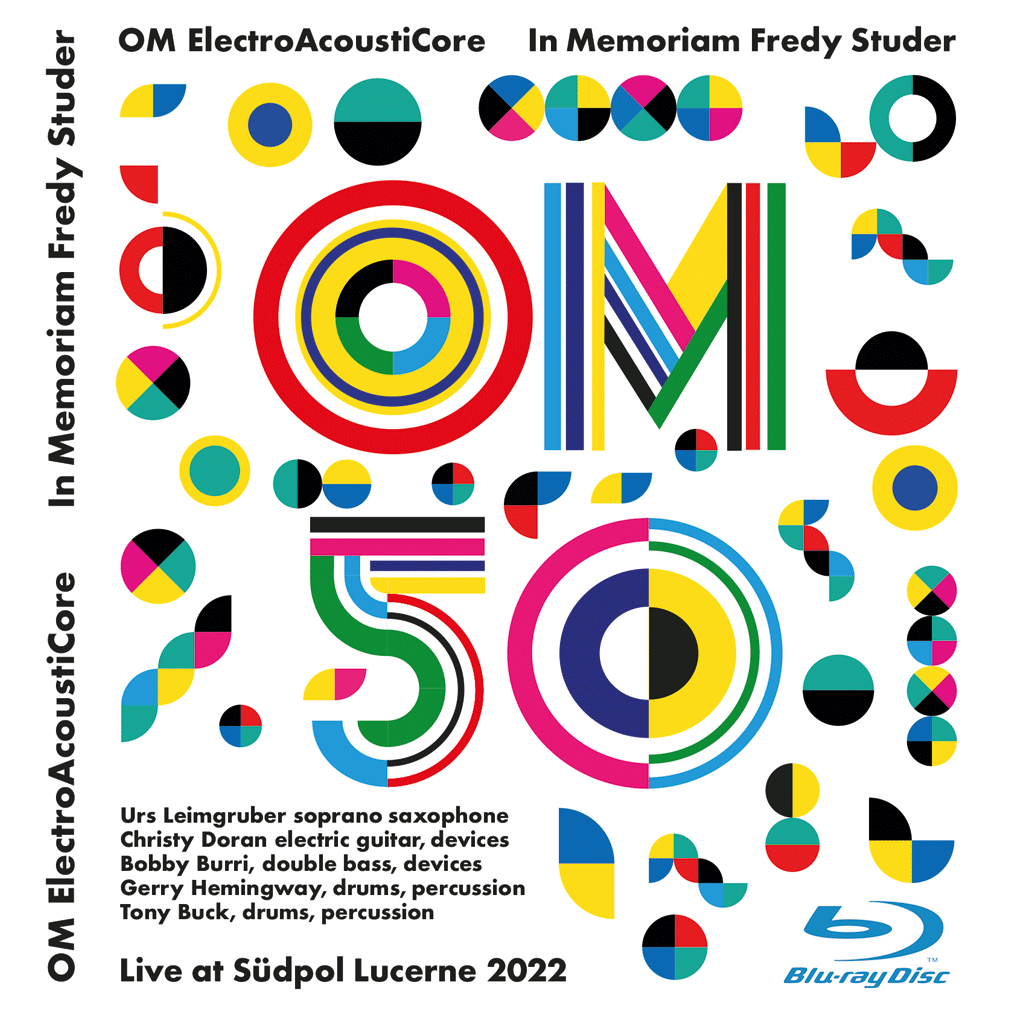

Release von OM50 In Memoriam Fredy Studer, im Eigenverlag, «Live at Südpol 2022» auf Video, blue-ray disc, ein historisches Dokument mit Bedeutung.

release of OM50 In Memoriam Fredy Studer, self-published, «Live at Südpol 2022» on video, blue-ray, a historical document of importance.

OM 50

1978

Electricjazz-Freemusic

2021

ElectroAcoustiCore

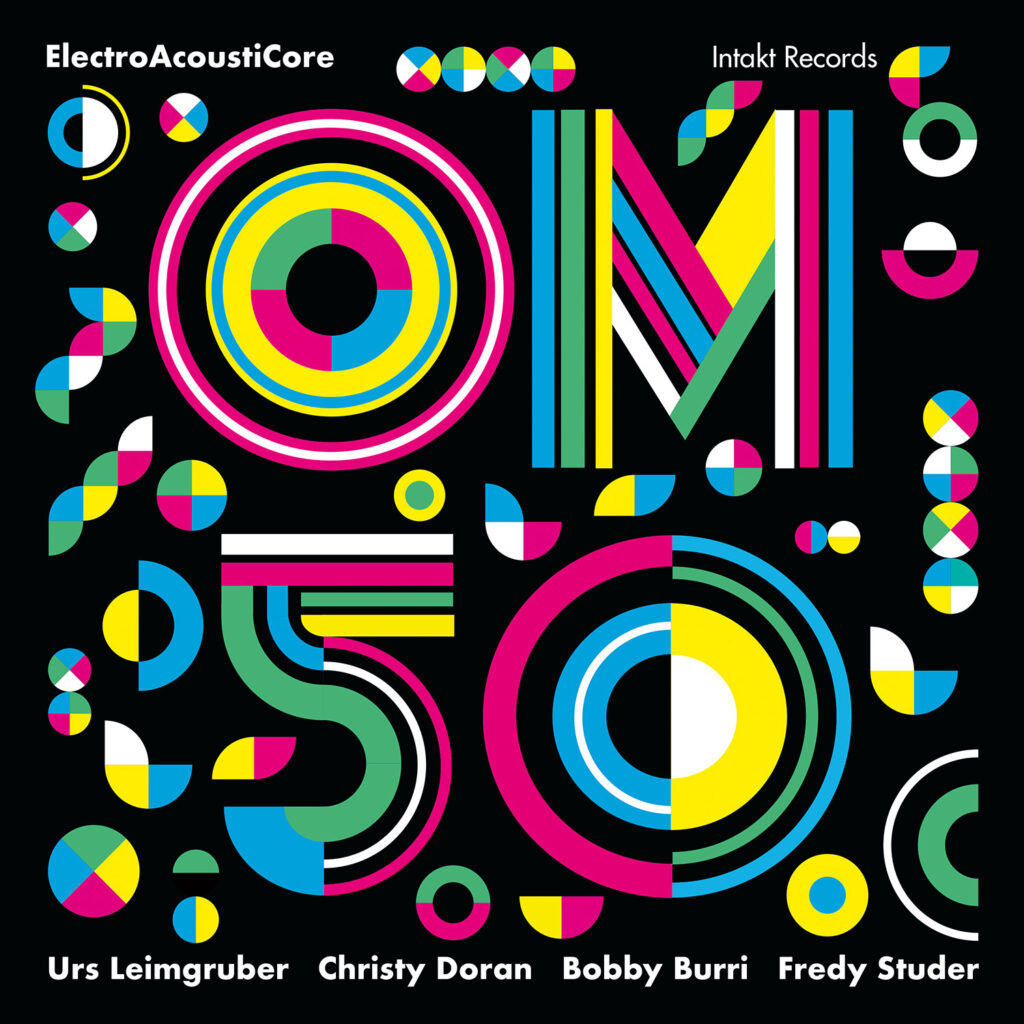

OM recorded a new CD called „OM 50“ in February 2022. The recording (by Roli Mosimann at Gabriel Recording, Stalden, Switzerland) will be released in September 2022 on INTAKT Records. In October and November OM will be on tour for the 50th anniversary with concerts through Europe! SEE LIVE

Photo by Thomas Gabriel

CD -Release Date September 16th, 2022

Linernotes by Jason Bivins , North Carolina , May 2022

„I often lose my place when listening to OM, the legendary quartet that’s been with us for half a century. There are moments all over their records when I find myself in an incredible polyrhythmic thicket or deep cosmic space, and I pause, thinking, “Wait, how did we get here?” That’s OM to me.

My baptism in their sound wasn’t initially at the source but a couple decades down the road, via the celestial guitar playing of Christy Doran. Next stop was a pair of sizzling ECM dates which introduced me to bassist Bobby Burri and percussionist Fredy Studer, which led me to hunting down vinyl copies of OM’s early Japo releases. A band that could play the gentlest pastorals, or free jazz teetering on the ledge, or cosmic funk, usually all on the same record? I was hooked.

It wasn’t long before I was exploring Fredy Studer’s wild cello trio, Urs Leimgruber’s solo sax and trio records, and of course, all the Doran I could find, from Corporate Art to New Bag and on. As a quartet and on their separate paths, they’ve got incredible reach. And so it’s worth asking a pretty big question on this important occasion: What makes this band so unique? You could answer a number of different ways, starting with the band’s name, which most folks might associate with chanting and meditation. That makes sense, but think more of the primal sound at the heart of the universe’s creation and you’d be closer to the mark.

And indeed, there is a kind of ongoing, ever-changing creative energy that characterizes OM’s music from their early sides all the way through their glorious return to performance about a decade ago at Willisau. Growth and permutation through cycles, the unquenchable desire to create the new in the heat of the moment.

To my ears, one of the things that remains freshest about this group is how they resist classification. Sure, let’s not overlook how deep they are as listeners, how much space they leave for each other, or how much technique and imagination they play with. But this isn’t a band that’s all that concerned with “hot solos” over thirty-two bars or with being emphatically free- jazz, jazz-rock, or much of anything else. As I’ve been listening back to various OM records lately, I’d answer the question about their uniqueness by pointing not to their various different permutations but to how consistently they’ve been able to balance four essential elements. And they’re each on abundant display on 50.

What stands out first is OM’s feel for contrast. Contrast between players, between approaches to the music, between colors, whatever you’ve got. Dip into “Fast Line,” for example, with its quick shifts between nimble rimshot grooves and deep sonic abysses. It’s organic and unpredictable, with Leimgruber alternating his tone and attack so subtly, and Doran creating huge electronic skies. Each time I listen, I lose myself in a different moment or a different musician’s contribution, each time finding new gems.

Which brings us to the second constant in OM’s sonic universe: surprise. Of course there’s surprise in all kinds of music, but what I hear in their playing over the decades is a willingness to recognize the moments of synchronicity in performance – that wondrous stuff that can’t be mapped out – and to latch onto them, following them wherever they go. Consider the wonder that is “A Frog Jumps In.” It’s an astonishing study in how much can happen when everyone’s playing with restraint and intention and huge ears. Leimgruber opens with the most marvelous passage of vocalized saxophone, setting up a space where all four musicians get as far from instrumental convention as they can. Glissandi, soft percussive patter, strangled squeaks, the whole thing a glorious sonic mandala that keeps pinwheeling through change after change.

Holding all these elements together, nobody overreaching or taking up too much space, that’s what makes OM’s music so much more vital than if everyone just cycled through heads and solos. There’s loads of expression, mind you, but the performances crackle because of that third prime element: tension. It’s there almost immediately on the opening track, “P-M-F/B,” palpable in its surging groove. In a helix of new tones and new angles, Leimgruber spools out plaintive lines, Doran sets up crystalline harmonies against the sound of metallophones, and the groove from Burri and Studer makes you feel intoxicated like you’re at some new ritual. Yet all this energy and imagination never descend into a mere bash or blowout; OM just keep converting it into new forms and moments with a vitality and urgency that most new bands can’t reach, much less ones of OM’s vintage.

Oh, and that last, crucial foundation of OM’s sound? It’s beauty. Partly because of their commitment to going where the music takes them, and partly owing to their longtime embrace of their own kind of lyricism, OM have never fallen into the “fierce-all-the-time” trap. Thankfully. When “Behind the Eye” fades in, I just swoon for those chiming chords in Doran’s world of loops, the perfect merging point for Burri’s arco, Leimgruber’s sculpted tones, and Studer’s pointillistic commentary. Things are even more ravishing on “Diamonds on White Fields,” with exquisite subtlety coming from Burri and Studer, and beautiful melodic interactions nestled between chimes and a marvelous distorted bass section.

Make no mistake, though – you could easily locate all these elements in any particular track. And that’s part of what makes this group magic. For goodness’ sake, the spooky voyage “Im Unterholz bei Kiew” could be a new soundtrack to Tarkovsky’s Stalker or something you dance around your kitchen to. I certainly don’t know of any other bands that have that kind of reach. With decades of growth and exploration, together and separately, OM are making their best music right now.“

A Retrospective (2006)

Linernotes by Peter Rüedi, Tremona, Switzerland, 2006

OM. Revisiting a Legend

„Can any good thing come out of Nazareth?” Nathanael asks Philip in St. John, I, 46. And can any good thing come out of Lucerne – if not first imported from elsewhere? When at the beginning of the 1970s, the OM quartet excited (in both positive and negative senses) first their homeland and then the rest of Europe with their „electric jazz – free music“, even those used to Swiss surprises rubbed their eyes.

A muscular drummer from the St. Karli quarter, vintage 1948, an electric guitarist, born 1949 in Ireland, who grew up in Lucerne, a powerful bass player of the same age, hailing from rural, back-of-beyond Malters, and a sax player and flutist whose parents used to run the local “Hotel Schiller”: at first glance this looked like the line-up of a band of music students allowed to let their hair down in the parish hall on Saturday nights. That Fredy Studer, Christy Doran, Bobby Burri and Urs Leimgruber all lived in or around town was one thing – but they also had the temerity to call their quartet OM, thus aligning themselves, at least in nomenclature, to the highes (or deepest) reality. For “OM” was not only the title of a record by John Coltrane, then already one of jazz’ patron saints, it represented no less than an Orphean primordial word, albeit of Indian origin: “The first vibration, that sound, that spirit which sets everything else into being. It is the Word from which all men and everything else comes, including all possible sounds that man can make vocally. It is the first syllable, the primal word, the word of Power.” (Coltrane in the liner notes to “OM”). In short, these backwater guys had guts, and it took some time (in Switzerland more than in neighbouring countries) for people to realise that they not only talked big but had something to say, that their music was strong as well as loud. Their message, shared by the Willisau Jazz Festival that Niklaus Troxler launched soon after (Willisau being Lucerne to the power of two): nothing is provincial except the fear of being provincial. Jazz was considered so exclusively an urban music that nobody thought to ask where all the great musicians in New York had come from.

“Electric jazz – free music” was a formula that described the quartet’s music perhaps more precisely than they themselves realized in the beginning. The point was the combination of genres. In 1969 Miles Davis recorded “Bitches Brew” and Tony Williams’s trio Lifetime (with Larry Young and John McLaughlin) released their first recordings. The next year Joe Zawinul and Wayne Shorter founded Weather Report. In 1971 McLaughlin formed the Mahavishnu Orchstra, followed by Chick Corea’s Return to Forever in 1972. Herbie Hancock’s “Head Hunters” was released in 1973. So much for the “electric” ingredient, this was their environment. Studer, Doran, Burri and Leimgruber belonged to a generation moulded by rock music: the Beatles, the Stones and – more than anyone! – Jimi Hendrix. To him they owed the Paulinian experience of discovering improvisation (the two concerts Hendrix played in Zurich in 1968, two years before his early death, had a profound impact on their generation, at least the open-minded part of it).

Another milestone was the encounter with free improvised music by the likes of Pierre Favre or Evan Parker, American “Great Black Music”, and, more proximate, the Beat Kennel-organised “Wiebelfetzer Workshop” with musicians such as Charlie Mariano, Peter Warren and John Tchicai. And, above all, Irène Schweizer. For a while the pioneer of free improvisation worked as a secretary for the cymbal maker Paiste in Nottwil (another out-of-the-way place) where Studer later succeeded Pierre Favre as “house drummer”. All four of them discovered free music (as well as ethnic styles and contemporary composition) after rock music. It became the source of open interplay, creativity, exploring the tension between sound and noise. Rock provided the power, and unsettled – and polarized – the audience at first. Jazz purists fled from too many decibels. Or, if they belonged to the radical free jazz camp, they wrinkled their noses at too much harmony and/or melody. Dynamically, OM did not spare their listeners, but unconditional destruction, what was once called “Kaputtspiel Jazz”, was not their method. Deep within the texture of their music they were weaving delicate nets and poetic spaces, although few were aware of it at the time.

In 1974 OM played in Montreux and released their first, self-produced record. Manfred Eicher liked it enough to encourage them to go on, offering the prospect of releasing their work on ECM’ sister label, JAPO Rccords. From 1976 he issued four OM records: “Kirikuki” (1976), “Rautionaha” (1977), “OM with Dom Um Romao” (featuring the former Weather Report percussionist, 1978) and “Cerberus” (1980).

The music on this CD documents an evolution and is therefore in chronological order: “Holly” and “Lips” are from the first album, “Rautionaha” from the second, and “Dumini” from the “Om with Dom Um Romao” record. “Cerberus” was transferred complete, for the simple reason that it is the most mature of the four. Studer/Doran/Burri/Leimgruber want to document OM’s history by using music that they can still identify with 25 years after the group’s break-up. And the freshness of the music is indeed arresting. The selection here avoids, very successfully, the pitfalls of cliché that make so many artefacts of the jazz rock era sound dated, bland, neither fish nor fowl. OM was a band, not an alliance of four lone warriors. A group that, in the course of a ten-year history, became ever more close-knit, with each member keeping his ego on a short leash. They knew that the whole was worth more than the sum of its components, if they avoided the obvious solutions and sought, instead, what the Grand Old Man of American jazz criticism, Whitney Balliett, defined as the core of all jazz: “the sound of surprise”. By avoiding and sabotaging routine (including the obligatory endless solos, the kind of relentless scale-grinding that a Coltrane in top form could render intriguing but certainly not his countless epigones) – and with an astonishing lack of vanity, the work of OM, once one of the leading European jazz ensembles, has remained fresh, thanks to the nerve, power and vitality of their music. Even though – no, because – they separated in 1982. Not that they had exhausted the common ground they occupied (to use a political phrase). The players have remained very much in contact in various constellations, encounters, musical contexts. But they also went their own ways – because the wise artist avoids routine proactively, at a point where nobody else is aware of the danger.